China’s Q-Ship Containerized Weapon System

Loosely stiched image of Zhong Da 79, the demonstration ‘Q Ship’, berthed in Shanghai. CLICK to Enlarge.

Putting weapons onto a merchant vessel is nothing new of course, and the concept of containerized missiles in standard ISO 40ft (12m) is very much in vogue. Iran, Israel, Turkey and Russia are among the countries to have already done this, or at least proposed it. Yet it remains novel and the latest Chinese vessel stands out in several important ways:

Putting weapons onto a merchant vessel is nothing new of course, and the concept of containerized missiles in standard ISO 40ft (12m) is very much in vogue. Iran, Israel, Turkey and Russia are among the countries to have already done this, or at least proposed it. Yet it remains novel and the latest Chinese vessel stands out in several important ways:

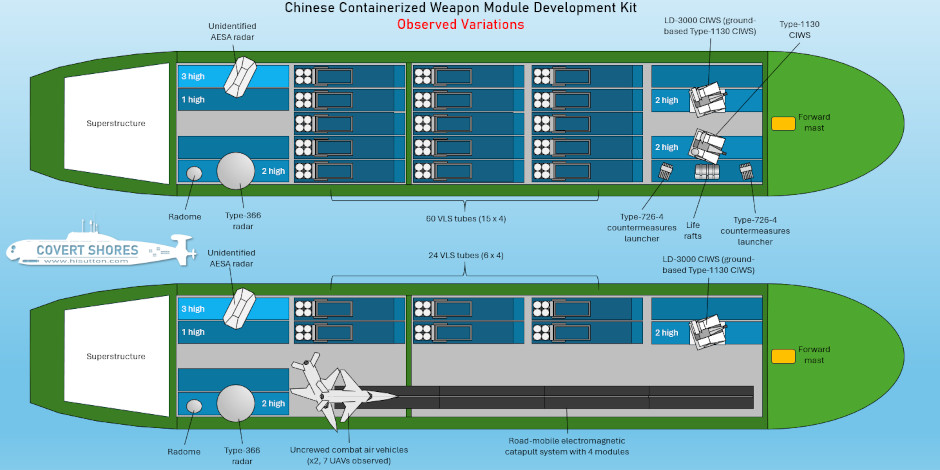

A) Its scale, completeness and sophistication are much greater than simply hiding a few missiles in containers. This system can potentially partly fill the role of warships including area air defence. The sensor fit, including modern frigate-level radars, is unique.

B) China has the investment and ambition to test these ideas at this scale. While other countries have stuck to slideware, mock ups and limited tests, someone in China can afford to deck out a ship with most or all of the elements. These are likely real systems (the weight of the close-in-weapon system (CIWS) was enough to distort its shipping container, so it is not a wooden mock-up, and the rest looks real) and including not one, but seven drone airframes. And several of the modules are powered, also challenging the suggestion that it’s a mock up. Demonstrations could be done a lot cheaper than what we are seeing. This ship is clearly for demonstration, but even if we accept that there is a degree of marketing and internal politics at play, it appears to be a serious project.

C) With China there is the additional context of an anticipated invasion of Taiwan. There is a higher likelihood of these being part of a wider plan, and thus may progress from demonstration to real capabilities.

Below we will look at some history of containerized weapons on merchant ships, look more at the drone carrier angle, and consider the implications for a potential war in Asia.

CLICK to Enlarge.

Zhong Da 79 – Demonstration ‘Q Ship’

The vessel outfitted outside Hudong-Zhonghua shipyard in Shanghai is Zhong Da 79 (MMSI: 412469140), an otherwise unremarkable 97 meter long 16 meter beam cargo ship built in China. She sailed from a small shipyard in Jiulongjiang South Harbour on the Jiulong River (vicinity 24.4346 117.8391), Longhai, on November 4th 2025 and arrived at the shipyard on November 8th. The containers were lifted onto the deck weeks after she berthed in Shanghai.

Zhong Da 79, the demonstration ‘Q Ship’, berthed in Shanghai.

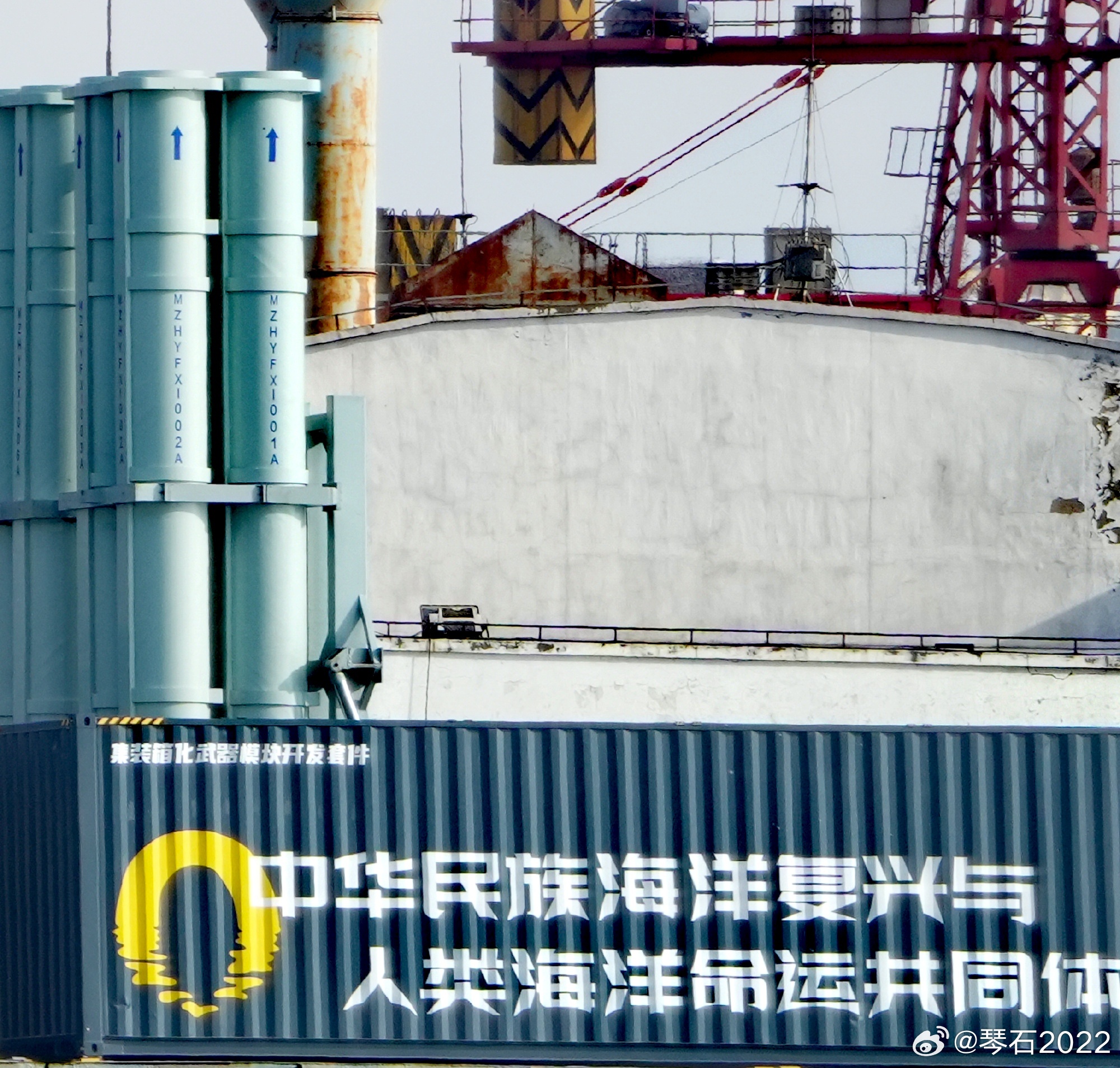

The containers are marked top left with Containerized weapon module development kit (集装箱比武器模块开发套件). A larger logo and text in the center of each container can be translated as The Chinese nation’s maritime rejuvenation and the three-dimensional maritime community plan (中华民族海洋复兴与 人类海洋命运共同体计划). Althoigh such slogans are not characteristic of the Chinese Navy (PLAN), this implies a wider government initiative of some sort.

The text on this VLS container reads ‘Containerized weapon module development kit’ top left and then ‘The Chinese nation’s maritime rejuvenation and the three-dimensional maritime community plan’ in the middle.

Amidships the vessel was initially fitted with 15 quad-launch missile containers (totaling 60 tubes) – it was later reduced to 24 when UCAVs were added. These are of the typical fold-down type to fit inside the container. The tubes are approximately 7 meters long, but the arrangement likely allows longer tubes. We should note that although the container is 12 meters long, the missiles need to fold forward for storage so the maximum length is probably around 8 meters long, depending on their diameter and the size of the frames.

They appear outwardly similar to those observed being loaded into the universal vertical launch system (UVLS) fitted to the Chinese Navy’s (PLAN) Type-052D Luyang II class destroyer. This implies that they can carry a range of missiles including the HHQ-9 long-range SAM (roughly equivalent to the Russian S-300 system), YJ-18 supersonic anti-ship missiles (similar to Russian SS-N-27 SIZZLER) and CJ-10 land attack cruise missile (roughly a Tomahawk). It is also possible that anti-submarine missiles and smaller SAMs could be loaded.

The missile tubes have individual numbers on them starting in the first row, from starboard to port, from MZHYFXI001A and MZHYFX1002A. In due course these serials may provide further hints.

The ship also mounts two large radars, one a Type-366 over-the horizon radar mounted on two containers, and the other an unidentified two-faced AESA mounted higher up on three containers. Their positioning likely creates blind spots, but they would all the same offer frigate-like levels of coverage.

The containerized radars (left) and close-in-weapon-systems (CIWS) plus countermeasure launchers and life rafts (right)

On the forward section two close in weapon systems (CIWS) are mounted on double stacked containers. One is a standard shipboard Type-1130 CIWS, and the other a land-based LD-3000 version. The latter appears to be mounted on top of the container with only the ammunition within. Countermeasures launchers and additional life rafts are also shown. After the initial arrangement described above, the vessel was reconfigured to carry a UCAV launch catapult.

Not A Q-Ship In The Proper Sense

The common notion is that shipping container weapons systems are for concealment, allowing a surprise attack on enemy coasts typically by launching overwhelming salvos of cruise missiles. A bit like a cross between Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb and an Arsenal Ship. The concept has some merit, but is quite different from what we are seeing here. Although the containers may offer some concealment, they appear principally to be for ease of logistics and attachment to the ship. And a merchant ship with a large frigate-grade dual-face rotating AESA radar is hardly discrete.

And the new design is distinct from the classic Q-Ship concept. Those were conceived in World War One as merchant ships with concealed weaponry designed to lure German U-Boats to attack them, so that they could in turn be sunk.

In modern parlance Q-Ship is generally applied to any disguised merchant ship intended to launch attacks. That too doesn’t quite fit this vessel, where the containers are used for practicality rather than disguise, but in the absence of a better term Q-Ship has caught on.

A Brief History Of Precursors And Similar Concepts

Armed merchantmen go back to the age of sail, but the exciting concept of standardized shipping containers is post World War Two. For years they were confined to primarily civilian use. Then during the Falklands War in 1982 Britain converted a merchant ship, the Atlantic Conveyor, to ferry Chinook helicopters and Harrier/Sea Harrier jumpjets to the South Atlantic. This conversion involved using shipping containers to create a makeshift shelter. The vessel gained fame when it was lost during an Argentinean Exocet attack. This led to a raft of concepts of how to better adapt merchant vessels to the stresses of war, especially in the UK where the Falklands experience was still top of mind. Most of these made use of shipping containers in some way including in some cases to house missiles. Yet, being a wartime contingency, none seem to have entered service.

The Atlantic Conveyor introduced ISO standard shipping containers to the playbook, but they were only used for shelter, not weapons.

Much more recently both Iran and Israel have demonstrated launching ballistic missiles from merchant ships (or merchant vessel converted auxiliaries at least).

In 2017 Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) tested its LORA missile from a merchant ship in the Mediterranean. A second test was conducted from another vessel in 2020. While the first launch utilized a truck mounted system, LORA is advertised as containerized and the test was always taken as a demonstration of the container capability. In 2024 Iran launched a Zolfaghar short range ballistic missile (SRBM) from the I.R.I.S. Shahid Mahdavi (110-3). Since then, missile manufacturers periodically present variations of their products hidden in shipping containers.

Iranian test launch from Shahid Mahdavi (left), and Israeli LORA test (right).

Modern containerized missile systems include the Russian Klub (Kalibr) system (left) and Turkish Kara Atmaca (right).

Drone Carrier Cross-Over

One capability being shown is as a drone launcher, with seven airframes seen. The airframes have been under wraps, but their general characteristics can be discerned. Six are a UCAV type design, with stealthy lines and a single jet engine buried in the fuselage, and the other is a propeller powered ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) platform.

Drone carriers are an increasingly important category of future warships. As well as adding fixed wing combat drones to light aircraft carriers and assault carriers, such as China’s Type-076 Yulan class, purpose-built designs are emerging. Iran has also experimented with converting merchant vessel hulls into drone carriers with the large I.R.I.S. Shahid Bagheri (C-110-4) undergoing conversion in 2022/23.

China is ahead with two newly built flat-top drone carriers already floated. The first, measuring 100 meters by 25 meters, was built at the Jiangsu Dayang Marine Equipment shipyard on the Yangtze River in 2024. Few details are available, but it appears linked to war gaming. The second, Zhong(/Zhono) Chuan Tan Suo 01, is larger 200 meters long and 40 meters across design which was launched at Longxue in 2024. This has been observed operating near to where other drone vessels, including underwater drones, are tested. Both are likely semi-commercial projects however and their role in the Chinese Navy (PLAN) is unclear.

China’s first drone carrier (left, forward deck visible), and the larger Zhong Chuan Tan Suo 01 (right).

The UCAVs bear a strong resemblance to displayed versions of the Feihong FH-97 reconnaissance and strike drone (version with top mounted intake), but with a slightly different wing plan. It’s logical to assume that these aerial drones are intended for combat missions.

The UCAVs have been observed loaded onto the starboard side of the ship, replacing over half of the VLS capacity. Two airframes have been seen aboard but if more of the VLS were removed there should be space to park the remainder. A crane would likely be needed to load them onto the launch rail. There is no question of landing them on the ship, except perhaps by parachute into the sea (which is not suitable for immediate reuse). We can take it therefore that unlike the dedicated drone carriers, this is for launch only.

A single piston engined surveillance drone similar to the U.S. military’s Predator, so possibly a CASC Rainbow CH-4, is also present. This aircraft appears to have a much wider wingspan which might pose challenges aboard such a small cargo vessel.

4 trucks connect together to provide a level take-off run for the UCAVs.

The UCAVs take off via a catapult system, likely electromagnetic (EMALS), mounted on four interlocking trucks. Resembling vehicles used at airports, these have finely controlled decks which can be aligned to create a flat take-off run even over undulating terrain. Similar concepts have been shared previously by Chinese defence firms. The use of trucks, rather than containers, suggests that they were readily available rather than optimal.

Implications For A Potential War In Asia.

It is difficult to fully envisage all the possibilities of how these might be intended to be used. Converted merchant ships generally aren’t fast enough to operate with warships as surrogates. And it’s hard to see these being particularly useful for convoy escort, or self-escort. The CIWS modules on their own possibly. The most obvious use as floating SAM batteries. These would be deployed in circumstances where geography, or other vessels, provide protection from subsurface threats, or where they are (despite the expense of modern SAM systems) expendable.

So at face value a ship like Zhong Da 79 could, during a hot war, act as a partial replacement for a frigate, particularly in the air defence role. It could not perform the same range of roles, or as well, but in the context of a cross-Strait invasion it could boost numbers and provide area air defence to vessels making the perilous crossing.

Although cargo ships are, in many respects, more survivable than warships thanks to their size and construction, they are also comparatively expendable. They may therefore be used in places where, until now, older and second-rate warships might have been considered. And because they are carrying much more modern systems, they may perform better.

The demonstration vessel, Zhong Da 79, is relatively small at under 100 meters in length. The containers could be placed on larger hulls which can carry more. There are many container ships in China which could, in basically the same configuration, carry over 200 missiles if the need was there.

The greater threat comes not from a few fully kitted out container conversions, but if the systems are distributed over many hulls.

It is even less clear how the UCAV role could prove useful since it is take-off only, which would limit the number and frequency of raids. UCAVs would have to be recovered on other carriers or back on land. Expensive strike drones only really add value when their operations can be sustained. With few exceptions, for a single strike missiles or one-way attack drones make more sense (and are cheaper). Their value is in their reusability. Thus being able to launch them but not recover them needs careful contrivance on circumstances to make sense. So while it could increase their range relative to land launch, it is a one time hit. In such a scenario land-attack cruise missiles might be a much more worthwhile bet. Other roles for the aircraft such as ISR or, theoretically, interception, seem even less credible. Drone carriers are interesting tio navies but this layout may be more the worst of all worlds rather than the best.

In some respects this concept seems to embody current thinking, yet in others it seems much less useful than at first might appear the case. In the West it can help update and sharpen our thinking regarding ships taken up from trade (STUFT) in wartime, and the roles of merchant vessels. But the answers we come to might be quite different from what we see here.

Related articles (Full index of popular Covert Shores articles)

China’s semi-submersible trimaran possible arsenal ship.

China’s semi-submersible trimaran possible arsenal ship.

Guide To Iran’s Navy & IRGC Drone Carriers And Similar Large Ships

Guide To Iran’s Navy & IRGC Drone Carriers And Similar Large Ships

Ceara; Brazil’s unique Submarine Transport Ship With Hidden Hangar, 1915 w/Cutaway

Ceara; Brazil’s unique Submarine Transport Ship With Hidden Hangar, 1915 w/Cutaway

Armored Stealth Boat used for car smuggling by Chinese organized crime. w/Cutaway

Armored Stealth Boat used for car smuggling by Chinese organized crime. w/Cutaway